Every spring, the Prairie Pothole Region (PPR) teems with duck calls and wings splashing on water. Shallow ponds glisten amidst rolling grasslands and farmlands, filled with waterfowl returning from the south to nest and raise their young. Spanning Montana, the Dakotas, Minnesota, Iowa, and southern Canada, the PPR is often called the cradle of North American ducks. Millions of mallards, pintails, and teal begin their lives here, and come fall, they embark on a migratory journey that ties together landscapes and people across an entire continent.

This migratory web depends on a mosaic of wetlands scattered from north to south that provide breeding habitat, migration pathways (or stopover sites), and wintering areas. Ranchers, hunters, recreationists, and conservationists work collectively to conserve habitats for future generations of waterfowl and people. Their conservation efforts receive funding through a postage stamp-sized piece of art known as the Federal Duck Stamp.

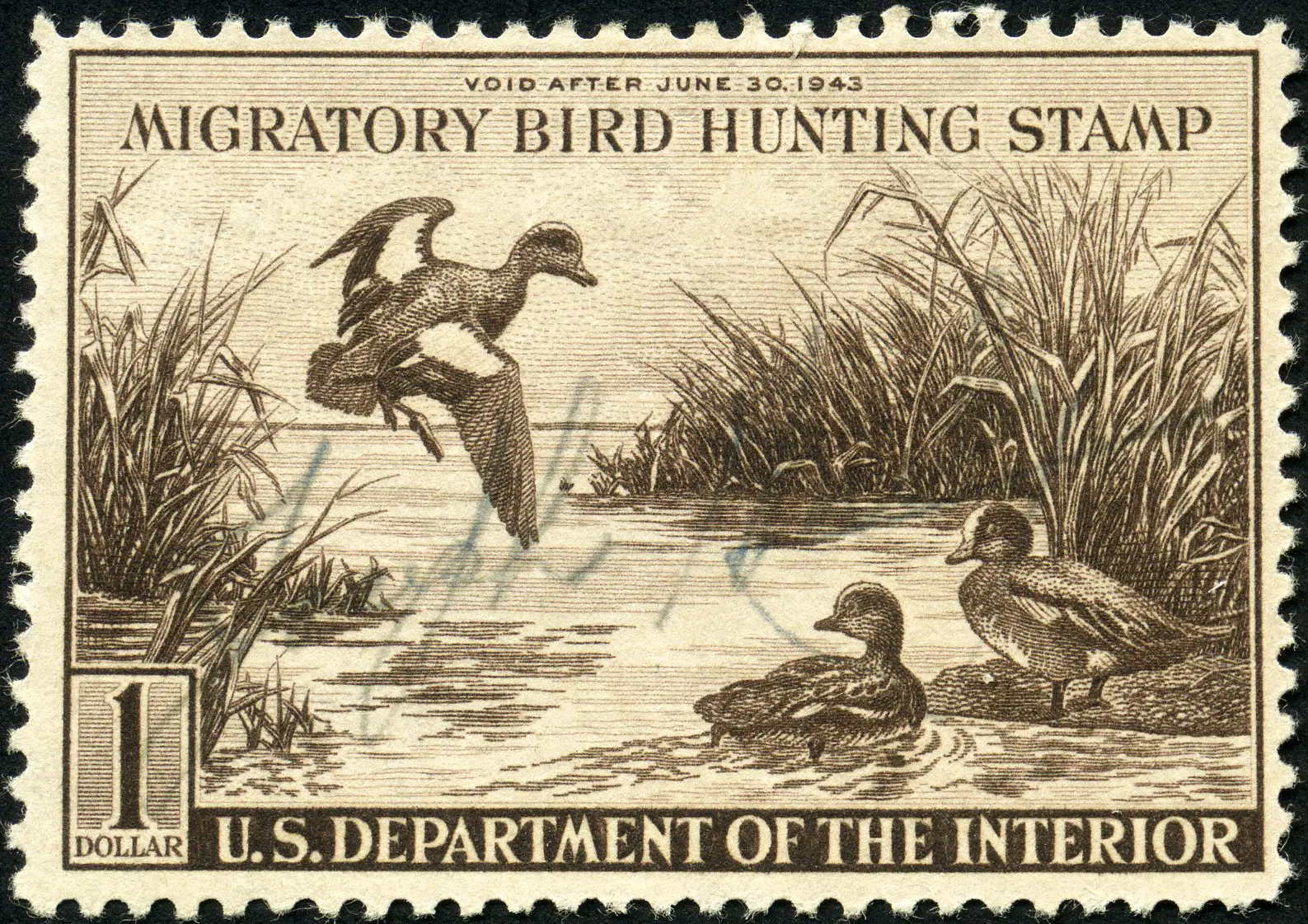

“1 dollar Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp – American Wigeons (1942)” by James St. John, CC BY 2.0

“5 dollars Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp – Canvasbacks and Decoy (1975)” by James St. John, CC BY 2.0

“7.50 dollars Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp – Mallards (1980)” by James St. John, CC BY 2.0

“7.50 dollars Migratory Bird Hunting and Conservation Stamp – Pintails (1983)” by James St. John, CC BY 2.0

Each year, a new painting graces the stamp. In 2025, three buffleheads skim over a moody wetland painted by Minnesota artist Jim Hautman, marking his seventh win in a tradition that uses art to spark conservation. Since 1934, sales of the stamp—required for all waterfowl hunters—have generated more than $1.3 billion to conserve wetlands and grasslands within the National Wildlife Refuge System and provide funding for voluntary private lands conservation. Beyond just hunters, the stamp also grants birders and recreationists access to all refuges across the country.

Those funds ripple far beyond the PPR, protecting habitat from the northern prairies to the southern bayous. Current projects that will increase wintering grounds for waterfowl that nest in the PPR include:

- Bear River Migratory Bird Refuge, Utah – $2,620,000 for 934 acres

- Red River National Wildlife Refuge, Louisiana – $14,600,000 for 3,285 acres

- Upper Ouachita National Wildlife Refuge, Louisiana – $35,238,000 for 17,023 acres

Although these places lie thousands of miles apart, each refuge represents vital habitat for birds migrating between the northern PPR breeding grounds and southern wintering grounds. Bear River hosts prime stopover territory for resting and refueling during migration. Red River and Upper Ouachita offer rich wintering habitat.

Just as birds rely on regions hundreds of miles apart, so too do people. Hunters in Louisiana depend on abundant springwetlands and grasslands that produce ducklings in the PPR. Banding studies reveal that at least 30% of ducks harvested in LA are produced (banded) in the U.S. PPR and over 70% of ducks harvested in LA are produced in the entire PPR region (U.S. and Canada combined), proving that healthy northern breeding grounds fuel the hunting culture and economy of the south.

Yet this web of life remains fragile. With 90% of the U.S. PPR privately owned, working lands stand among our greatest assets for continuing habitat protection. But these lands face significant threats. Agriculture grapples with rising costs, low market prices, and younger generations leaving to find work elsewhere. For grasslands and wetlands, conversion to cropland or development looms heavily as economic pressures outweigh conservation considerations.

Conservation easements—often supported by Duck Stamp dollars—help private land stewards maintain viable operations while preserving essential habitat. When managed sustainably, grazing livestock keeps grass green side up and safeguards open spaces. Supporting working land stewardship through conservation initiatives remains a win-win and the most efficient approach to enhance wildlife and rural economies.

At Bear River Refuge, cooperative agreements with local ranchers utilize cattle grazing in the management plan. Cattle often graze alongside the auto tour that Mark Brunson and his wife drive regularly. Mark, a scientist, professor, and avid birder, educates others on the importance of working lands. He’s dedicated the latter part of his career to collaborating with The Nature Conservancy to help livestock producers maintain open spaces.“The thing I worry most about is the working landscape. Ranchers go out of business, kids don’t want to continue, places get broken up into subdivisions, and that’s worse for wildlife. It’s worse for plants. It’s worse for a lot of things.”

Mark and his wife record every bird they see and find the most joy in spontaneous shared experiences with others along the way. He explains that refuges, especially those close to urban centers, provide easy access to nature and hands-on learning. They connect people to nature in ways cities can’t and they offer an excellent opportunity to engage with birds and ecosystems. “It’s been called America’s greatest idea, preserving wide open spaces, and I hope we don’t lose sight of that importance.”

The throughline between artists, ranchers, farmers, hunters, birders, and wildlife centers on the need for habitat everywhere. Our experience of wildlife in one place depends on the habitat, people, and culture of another. We need the ephemeral potholes in the north, marshes in the south, and stopover territories in between. We all depend on those wild spaces to nurture our young, rest and refuel on our journeys, and find shelter during the hard times. Conserving these habitats and keeping open spaces open, means supporting the programs that fund conservation and advocating for the stewards of working lands. So, buy a duck stamp, visit a refuge, or buy beef from a local rancher and become a guardian of America’s greatest treasure.